“Anything But Chardonnay”? There are good reasons for the popularity of Chardonnay.

Chardonnay is one of those grapes that became trendy to hate—along with Merlot—sometime in the middle of the first decade of the Millennium. It’s easy to see why, for several reasons. One is just a sheer glut of mediocre wine on the market. Two is…let’s not call them bad, but questionable winemaking practices. The third is the easiest to correct, yet least-often addressed: consumer ignorance.

This isn’t to say that the consumer is to blame for the last point. Indeed, prior the age of everything being a “Hey, Google” or an “Alexa…” away, it’s easy to see why people were often uninformed. Information was sometimes hard to come by. Sure, you could look up an encyclopedia entry on the Chardonnay grape. But it’s not really the same as having a multifaceted, three-dimensional view of the varietal, especially filtered through the lens of multiple wine columnists and amateur reviewers—you get my point. Let’s not get too meta here.

My point is, there’s a lot more to Chardonnay than both its deserved backlash and its current semi-pariah status. It’s an interesting grape, one that has a lot of things going for it. Part of the reason for its popularity in the first place is its chameleon nature. Traditionally, Chardonnay handles oak better than a lot of other white grapes. This has led, over time, to its being put through what is called malolactic fermentation (MLF).

Posts may contain affiliate links, so if you click an affiliate link and/or buy something you’ll support this blog and I’ll make a little money, at no cost to you. If you really care, you can read our full legalese blah blah blah.

“You need a real long finish that never quits

Like English treacle over hominy grits

A buttery flavor that goes on and on

With a hint of a grease and a nose too long

But you got to do it your own

With cigarettes and bad Chardonnay…”

-Graham Parker

If you tuned in last time to our discussion of acidity, you know that one of the primary acids in wine is malic acid. As its Latin namesake suggests, malic acid is responsible for the biting, aggressive acidity that you get from biting into a green apple. Lactic acid, on the other hand, is the acid in milk. Yes—milk is mildly acidic! But much less so than green apples. Furthering the dairy comparison is the fact that a compound called diacetyl—whose aromas and flavors are reminiscent of butter and butterscotch—builds up as a result of MLF bacteria.

So, you can take a green-apple, acidic Chardonnay and turn it into a buttery, smooth, (comparatively) low-acid white wine—simply by introducing a post-fermentation bacterial culture. If you do so while storing the wine in oak barrels—especially French oak barrels—you get a smooth, rich, Chardonnay with flavor notes of fig, vanilla, toffee, and buttered toast. This is the backbone of white Burgundy, and the reason that California winemakers began experimenting with Burgundian models of Chardonnay production in the 1970s.

Without wishing to cast aspersions or point fingers, though, California and Burgundy are two very different places. As global temperatures began to rise from the 1970s onward, California began to produce much “hotter” Chardonnays. It’s not uncommon now to find Chardonnays with upwards of 14% or 15% alcohol by volume. Add in 1 or 2 years’ worth of aging in American oak, and you have the genesis of the famous ABC backlash of the mid-2000s—Anything But Chardonnay.

It’s really not fair to the grape, though. After all, a wine gimmick or phenomenon is nothing more than the result of market forces. Anything But Chardonnay led to a remarkable duality by the early 2010s, wherein wineries would make an oak-driven, buttery Chardonnay alongside what became increasingly known as “virgin Chardonnay”—a Chardonnay untouched by either a barrel or MLF.

It’s quite enlightening, and fun, to put an apple- and lemon-driven “virgin” Chardonnay alongside its fig, toffee, and toast-defined twin, especially when considering that they came from the same vintage and producer!

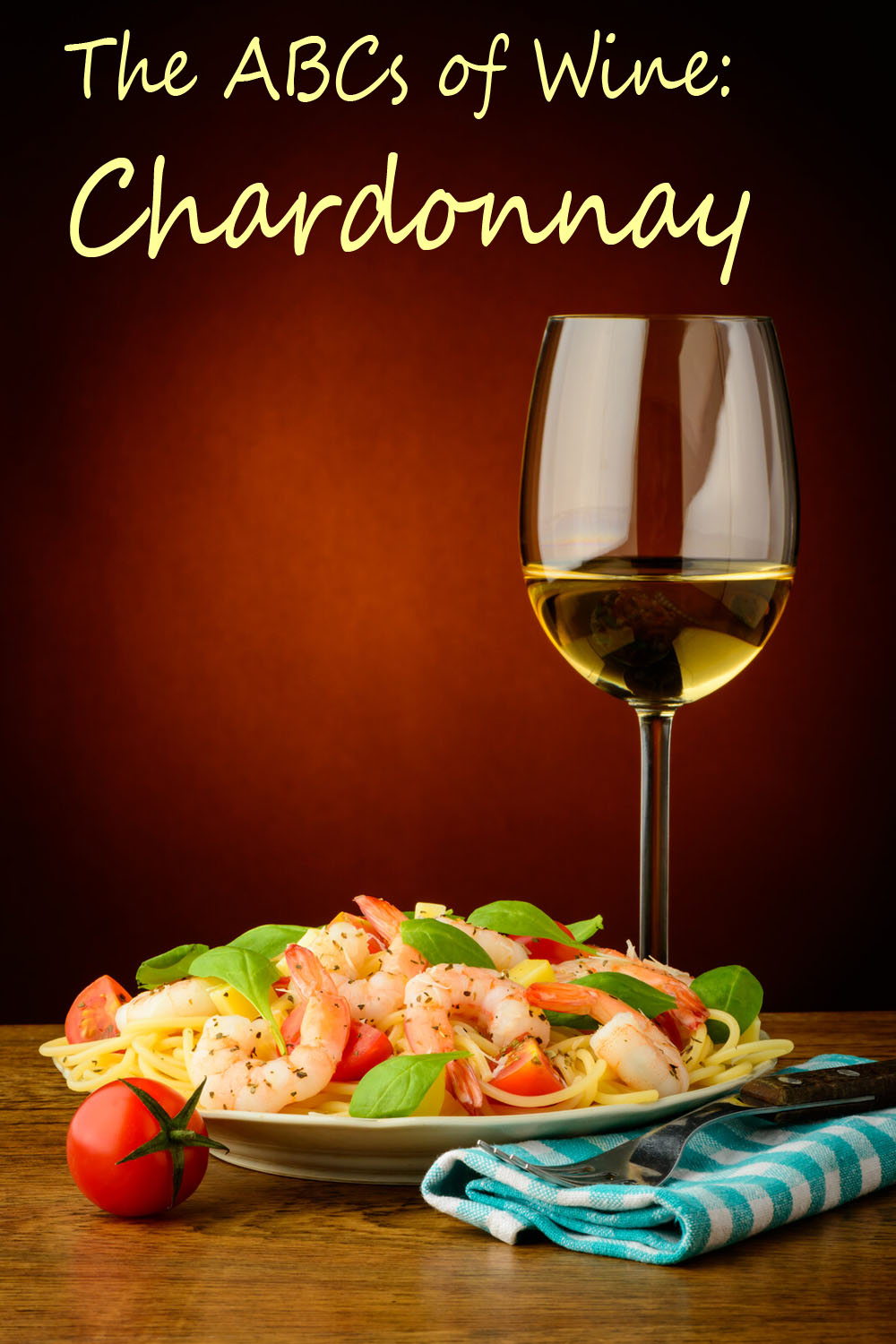

What to Pair with Chardonnay

They also pair with completely different things, as well. A “virgin” Chardonnay can be as light and crisp as a Pinot Grigio, and go alongside things like fish dishes, chicken piccata, or sharper vegetable such as Brussels sprouts or cabbage.

Buttery, oak-driven Chardonnays, on the other hand—as Warren and I have discussed numerous times—pair amazingly well with buttery (surprise) lobster and shrimp entrees, or rich cheese such as Brie.

The neat thing about Chardonnay is that no other grape pairs as well with such a wide variety of foods. The real trick is knowing how it was made and how it was aged. There is no one size fits all. It really is the type of grape that demands that you taste it first before making an assessment.

There is no backlash without popularity. Chardonnay attracted a lot of Americans to wine culture in the 1980s and 1990s. A generation later, it behooves us as a society to rediscover what made this grape so approachable and interesting. If you’re tired of oaky, buttery Chardonnays, see if your local wine store has an unoaked Chardonnay. (If you really want to impress them, ask if it’s been through MLF or not!) Change your wine; change your mind. Sláinte!

Buy some of these (or other) wines at Vivino and get 20% off with code WINELOVERSCU20 (first-time buyers in the US).

Leave a reply