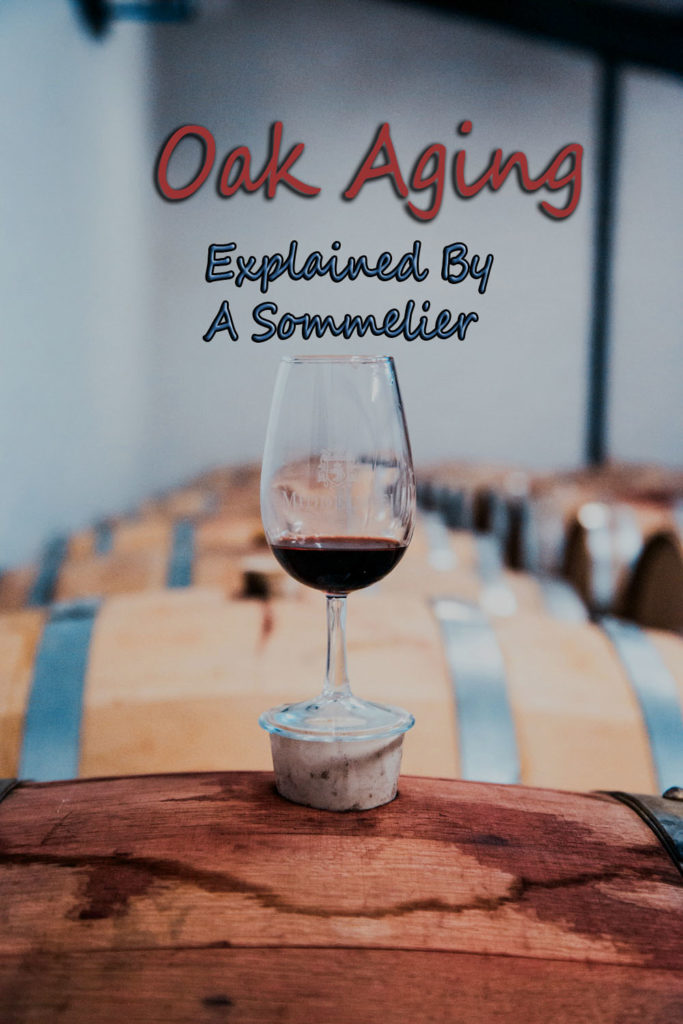

Judicious application of oak aging gives wine a more gutsy and tannic character—without destroying or impeding its natural fruit-driven facets.

I wanted to wait until after we discussed both acidity in wine and the Chardonnay grape before getting into oak aging. Although oak barrels primarily add flavor and aroma and structure to a finished wine, there are other factors involved as well that apply to both aforementioned subjects. As with other factors in the winemaking process, there are a lot of different variables and outcomes to note.

Posts may contain affiliate links, so if you click an affiliate link and/or buy something you’ll support this blog and I’ll make a little money, at no cost to you. If you really care, you can read our full legalese blah blah blah.

Why Oak?

Historically, winemakers used oak barrels for storing wine because, well, that’s all that was available. Nowadays winemakers can choose to leave wine in concrete or stainless steel tanks, which basically prevents the wine from aging. Oak still remains in use for more than just traditional reasons, however. The wood used to make oak barrels is porous. So it lets in small amounts of oxygen, much as a cork lets oxygen into a wine bottle. With a barrel, the entire surface area is porous, accelerating the aging process and thus the development of the wine.

Heavier red wines, such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Shiraz, can stand up to quite a long time in oak due to their overall tannic structure. Oak has tannins of its own as well. Some medium-bodied red wines actually gain a heavier-bodied nature due to being kept in oak. Spanish and French Garnacha/Grenache, for example, is heavier-bodied than it would be if bottled immediately post-fermentation. Judicious application of oak aging gives it a more gutsy and tannic character—without destroying or impeding its natural fruit-driven facets.

Most white wines are not kept in oak. Generally speaking, the lighter the white wine, the less likely it is to be kept in a wooden barrel. There are exceptions, of which Chardonnay is the most notable. As previously discussed, Chardonnay is a chameleon of a grape. It can be done in a variety of ways, from completely unaged to a more “oak-and-butter”-driven style.

The “oaky” and “buttery” characteristics go together hand in glove, and with good reason. The vast majority of oak-aged Chardonnays undergo malolactic fermentation, or MLF (which you may remember from the Chardonnay article itself). This has the twin result of softening the green-apple malic acid into lactic acid, which is found in milk, and creating the buttery-smelling-and-tasting compound diacetyl. It’s possible—and not uncommon—to put a stainless-steel-kept Chardonnay through MLF. But it’s extremely rare to forego MLF with an oak-aged wine. It’s easy to imagine why. Put together harsh malic acid and strong tannic structure, and you’d probably have yourself a nearly-undrinkable Chardonnay.

So besides micro-oxidative aging, adding tannic structure, and buttering up our Chardonnays, what else is oak useful for? Depending on the age—and provenance—of the barrel, a winemaker can impart a variety of flavors to a wine.

Flavors Added by Oak

French oak, by and large, adds a more nuanced and subtle flavor palette. Typical aromas and flavors associated with new French oak include fig, toffee, caramel, and toast. (The latter should come as no surprise. The inside of the staves that make up the barrel are toasted prior to cooperage, or assembly of the barrel.)

New American oak, on the other hand, is going to have more stereotypically woody aromas and flavors. While these can be overpowering in a white wine, in a red wine they can add notes of bourbon, vanilla, tobacco, and pipe smoke—all of which Warren and I have mentioned at some point or another in our reviews of various red wines.

You may have noticed my emphasis on the flavors imparted by new oak barrels. This is because a given barrel has anywhere between three to five years’ worth of use before it stops imparting flavor, aroma, and tannic structure to a wine. This doesn’t mean it has to be disposed of at that point, however!

Wine barrels are quite expensive—sometimes over a thousand dollars apiece—and winemakers are careful to get as much use out of them as possible. A common practice is to use a mixture of new and old oak—new oak to add flavor and tannin, old oak simply for aging purposes alone—and then blend the two together at the end of the aging process. (What with the backlash against oaky Chardonnays, many winemakers opt for a 50/50 blend of oak-aged and stainless-steel-kept Chardonnay, as well.)

Food Pairing

One last good thing about oak aging is that favorite topic of mine—food-friendliness and food pairings. We’ve noted that oak often adds tannin to wine. Within plant systems, the family of chemicals called tannins holds proteins together and keeps them from moving around too much. This is why red wine and cheese pair so well together. The tannins in the wine bind to the protein in the cheese, making the flavors of the wine seem to pop out dramatically.

This means that oak-driven wines can sometimes be even better with food than their stainless-steel counterparts. If you don’t believe me, try a really rich and buttery lobster dish alongside a stainless-steel Chardonnay and an oak-aged, buttery Chardonnay. Or, better yet, put a sirloin steak alongside an unaged Pinot Noir and an oak-aged Cabernet Sauvignon. None of the four would be what I would call a bad pairing. However, I think you’ll find that two of them will be objectively better, and will make you glad our medieval ancestors stumbled across the oak tree as a vessel for wine storage.

Buy some of these (or other) wines at Vivino and get 20% off with code WINELOVERSCU20 (first-time buyers in the US).

Leave a reply